The science behind red lakes

Everyone’s seen blue lakes and green lakes. Some deep or large lakes, like Lake Superior, can even look like an inky black. But have you ever seen a red lake?

Let’s examine the science behind scarlet water in one Minnesota lake and around the world.

A microscopic mystery

Last week, a colleague called and said that ice anglers on Fish Lake near Windom, Minnesota, were reporting that the lake had shifted from green to purplish-pink—almost a red color.

That’s not normal. DNR Fisheries quickly collected a water sample and sent it to the Science Museum of Minnesota for analysis.

The game is afoot

We poured the water through the fine mesh of a plankton net to concentrate whatever might be in there and put it under the microscope.

It was red!

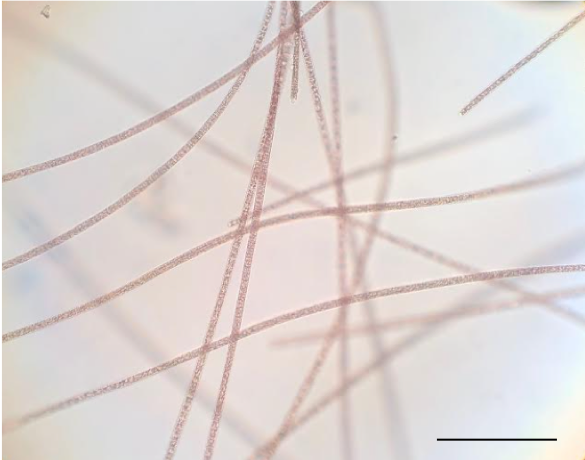

A cyanobacterium, Planktothrix rubescens, was growing at bloom levels and turning Fish Lake red. Planktothrix rubescens is not uncommon in Minnesota lakes.

It grows in little filaments that you can almost see with your naked eye. It’s been reported elsewhere growing in high abundance under the ice or right after ice melts—and, yes, it turns lakes red!

The red comes from a pigment called phycoerythrin that helps Planktothrix rubescens gather what little light penetrates below the ice. It can also control its buoyancy and will rise to the light when an ice hole is drilled. And like other cyanobacteria, we need to be careful around Planktothrix rubescens when it blooms.

Planktothrix is known to produce a liver toxin called microcystin. Small amounts may make your skin itch. And while most humans won’t drink from a nasty lake, animals will. Dogs and livestock die almost every year in Minnesota from cyanotoxin poisoning.

Different deductions

Fish Lake was my first experience with Planktonthrix rubescens, but I’ve seen other red lakes. In Mongolia, the landscape is so arid that some lakes turn super salty. In those “hypersaline” lakes, a “green” alga called Dunaliella salina turns them red.

Dunaliella has a red pigment called B-carotene that masks the “green” of its chlorophyll. That same red pigment is responsible for turning flamingoes pink as they filter feed on Dunaliella in similarly salty lakes on the plains of Africa and South America.

The other red lake was right in the backwaters of our St. Croix River. A reddish sheen on the placid surface looked very out of place and prompted some sampling.

Under the scope, we found the culprit.

Not a cyanobacterium, not a “green” alga, but a small type of algae called a euglenoid—Euglena sanguinea. Happily swimming around, colored red by the pigment astaxanthin, and taking advantage of extra summer nutrients and the morning sun. My Ph.D. mentor once got a panicked call from a cemetery whose pond had turned red. Fortunately, the fear that graves were leaking blood was not realized. Just a microscopic alga—the same Euglena sanguinea—turning another lake unexpectedly red!

Did you enjoy this watery, scientific mystery? Learn how to test water quality with this at-home science activity.