Race and racism

One's a myth. The other is most definitely not.

It's a conversation that we, as Americans, need now more than ever. Yet, in these divided times, it's difficult to get past each side's talking – or is it shouting? – points.

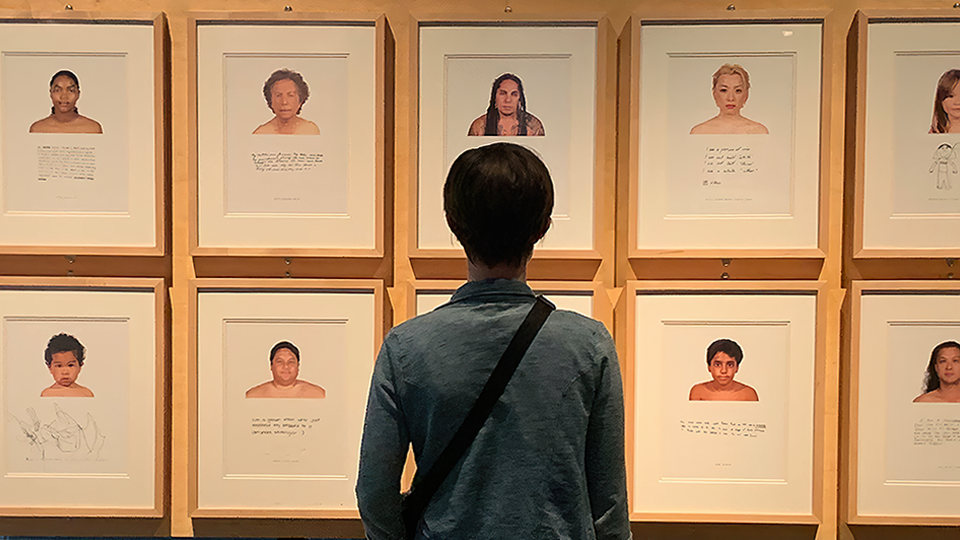

What we need is a safe place, one based not on opinion, but facts and, yes, even science to at least spark a discussion. And, in an ever-evolving exhibit called "RACE: Are We So Different?" it's right here in St. Paul at the Science Museum of Minnesota.

"Biologically, race doesn't exist. But racism is as real as it gets," says Liza Pryor, the museum's experience development process leader.

"We have to use our privilege to create change."

First opened in 2007, the 5,000-square-foot exhibition has traveled to some 60 cities across America. It's so popular that the museum built another just like it, as well as two half-size and three mini versions for smaller venues.

The one now back at the museum will, by January, cover new subject matter, including more local stories, a section on mass incarcerationt, and a memorial to the worst possible outcome of racism: violence and even death.

"We all come from the same ancestor. Any differences in the way we look is about place, not race," says Joanne Jones-Rizzi, vice president of science, equity, and education at the museum.

"We're not afraid of people pushing back against us."

The exhibit's premise is that race is purely a human invention, and only a few hundred years old at that. The idea's rise – and its stubborn hold on us – is tied to power and hierarchy, with one group of people using it to dominate others.

White Americans, in an effort to justify slavery, actually enlisted science, with crude instruments like the one used to measure skull size, to prove the differences among us. In fact, the American Anthropological Association, in an effort to right its role in some of those misguided efforts, is a sponsor – and partner – in the exhibit.

"Truth is, there's more variation within a racially identified group of people than between any of those groups," says Robby Callahan Schreiber, access and equity director at the museum.

"It's helped the science museum, itself, start on our own path to change."

The results of these manufactured differences are shown in stark detail in the exhibit's various displays.

In one, four stacks of money show how racial discrimination has led to a wide discrepancy in wealth in our country. White America boasts the tallest stack of bills, with an average median net worth in 2013 of $132,483. Latinos come in at $12,450, and Black Americans just $9,211.

Another display shows how the U.S. Census would've counted a group of Macalester College students over the years. One young woman would have marked herself a Slave in the 1800 census, a Mulatto in 1920, and a Negro in 1960.

Yet another display asks you to identify, from photos of various people and voice recordings, the speaker. Could you tell a Black voice from an Asian voice or a White voice from a Latinx voice?

"We're not responsible for creating a change in everybody," says Alison Rempel Brown, president and CEO of the museum. "We're just responsible for giving people the opportunity to change."

Read more about this topic at smm.org/start-conversation.